I. Precision Grading and Finishing

Achieving perfect grades and smooth finishes is a hallmark of an advanced operator, requiring a delicate touch and keen understanding of the machine's capabilities.

1. Fine Grading with the Bucket:

Beyond simply digging, the excavator bucket can be used for highly precise grading.

Feathering Controls: The key is to "feather" the joystick controls, making small, incremental movements of the boom, arm, and bucket curl simultaneously. This allows for shaving off thin layers of material.

Bucket Angle Management: Maintain a consistent, shallow bucket angle (often just a few degrees from horizontal) to act like a large trowel. The cutting edge should be slightly proud of the bottom of the bucket.

Blade-Like Action: For extremely fine finishes, some operators will tilt the bucket to use its side as a mini-blade, especially effective for backfilling around utilities or spreading granular material.

Laser and GPS Integration: For ultimate precision, experienced operators leverage integrated laser or GPS grading systems. These systems provide real-time feedback on bucket position relative to the desired grade, significantly reducing the need for manual grade checking and improving accuracy on complex contours. Understanding how to interpret the in-cab display and adjust movements accordingly is critical.

2. Spreading Material with Control:

Even Distribution: Instead of dumping piles, experienced operators can use the bucket to evenly spread material (e.g., gravel, topsoil) in thin layers. This involves a sweeping motion while gradually extending the arm and opening the bucket.

Back-Dragging: Utilizing the flat back of the bucket, operators can "back-drag" material to achieve a smooth, level surface, much like a dozer blade. This is particularly useful for final compaction passes or preparing a base layer.

3. Contouring and Shaping:

Slope Development: Creating uniform slopes requires a steady hand and consistent boom/arm movements. Operators must visualize the slope and execute smooth, continuous passes. The use of a "batter board" or string line is essential for consistent results.

Swale and Berm Creation: Crafting drainage swales or protective berms involves precise depth and angle control, often blending multiple passes. This requires a deep understanding of hydraulic flow and responsive manipulation of the controls.

II. Advanced Digging Techniques

Moving beyond simple trenching, complex digging scenarios demand nuanced approaches.

1. Blind Digging (Working without Direct View):

Reliance on Instruments and Spotters: When digging below the line of sight (e.g., deep foundations, cutting under an existing structure), operators must rely heavily on depth indicators, laser/GPS systems, and highly skilled ground spotters.

Communication Protocols: Establish clear, concise communication protocols with spotters, often using two-way radios and agreed-upon hand signals. Confirm each command before execution.

Systematic Approach: Dig in small, controlled sections, continuously checking measurements and confirming clearance with the spotter. Avoid aggressive movements.

2. Trenching in Challenging Conditions:

Wet/Sloppy Material: When digging in wet or soupy soil, the bucket needs to be curled quickly to prevent material from spilling. Operators learn to "milk" the bucket by quickly closing it to get a full load.

Hard/Rocky Ground: For highly compacted or rocky ground, experienced operators utilize a technique of "ripping" with a single tooth or "rocking" the bucket to break up material. This conserves tooth wear and reduces strain on the machine. Heavy-duty buckets and specialized rock teeth are often employed.

Benching and Step Cutting: When digging deep, wide excavations, operators can create stable benches or steps, not only for safety (preventing cave-ins) but also to provide stable working platforms for the excavator as it progresses downwards. This requires careful planning and execution.

3. Digging Under Existing Structures:

Underpinning Techniques: When excavating for underpinning, precision is key. Operators must understand the load-bearing points of the structure and dig carefully, often in sections, to expose footings without compromising structural integrity.

"Keyhole" Excavation: For minimal disruption, operators can use the bucket to dig precise, small openings (keyholes) to access specific points, such as utility connections, without a full-scale excavation.

III. Material Handling and Placement

Excavators excel at material handling, but advanced techniques elevate efficiency and safety.

1. Precise Load Placement:

Truck Loading Efficiency: Experienced operators can load dump trucks with minimal spillage and optimal weight distribution, using a smooth, continuous swing and controlled bucket release. This reduces cycle times and prevents overloading/underloading trucks.

"Placing" Material: Rather than just dumping, operators can precisely place granular material (e.g., aggregate for backfill) or cohesive material (e.g., clay for compaction) exactly where needed, minimizing secondary spreading or shaping.

Loading Hoppers/Feeders: Carefully positioning the bucket to minimize impact and maximize flow when loading material into hoppers or conveyors requires a skilled hand and spatial awareness.

2. Lifting and Setting Objects:

Proper Rigging: While excavators are not cranes, they are often used for lifting objects. Experienced operators understand the importance of proper rigging, using appropriate slings, chains, and lifting points. They must know the weight of the object and ensure it's within the excavator's lifting capacity (often using a lift chart).

Load Stability: Ensuring the load is balanced and stable before lifting is crucial. Avoid swinging loads over personnel or structures.

Smooth Movements: Execute lifts with smooth, controlled movements to prevent swinging, jerking, or dropping the load. Coordinate boom and arm movements for vertical lift.

"Feeling" the Load: Experienced operators develop a "feel" for the machine and the load, sensing stability and potential issues through the controls.

3. Demolition Techniques (Controlled Demolition):

Strategic Undermining: For controlled demolition, operators learn to strategically remove supporting elements to guide the collapse of a structure in a predictable manner. This requires structural understanding.

Material Separation: As structures are demolished, experienced operators can simultaneously separate materials (e.g., rebar from concrete, wood from metal) into different piles for recycling, improving efficiency.

Dust and Debris Control: Using the bucket to push down material or water sprays to control dust during demolition.

IV. Machine Maneuverability and Stability

Operating an excavator effectively in confined or challenging spaces requires mastery of its unique movement characteristics.

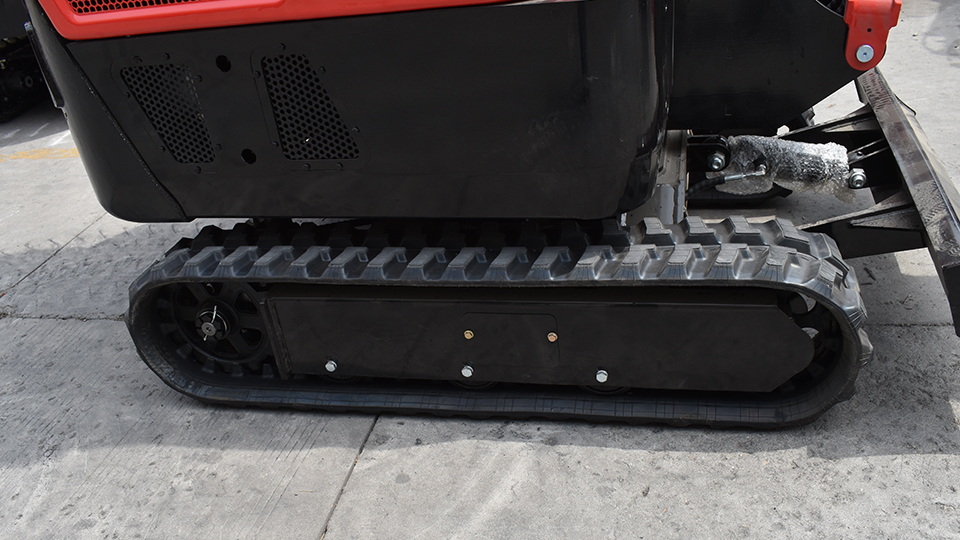

1. Operating on Slopes and Uneven Terrain:

Maintaining Stability: Always position the tracks/wheels to maximize stability. When traveling up or down slopes, the heaviest part of the machine (boom and bucket, if empty) should typically face uphill.

Bench Cutting for Stability: When digging on a steep slope, an experienced operator will often create a level bench for the excavator to sit on, ensuring stability and optimal digging performance.

Minimize Turns: On slopes or soft ground, make turns as wide and gradual as possible to reduce stress on the undercarriage and maintain stability.

2. Operating in Confined Spaces:

Short-Swing Models: Operators of short-swing or zero-tail-swing excavators leverage their design advantages for work in tight urban environments or alongside existing structures, preventing the counterweight from swinging into obstacles.

Precise Articulation: Utilizing the boom, arm, and swing functions in a coordinated manner to dig and dump material within a limited footprint, avoiding contact with surrounding objects. This often involves "truck spot" loading where the truck is positioned very close to the dig area.

3. Counter-Rotation and Spot Turns:

Tight Turns: For tracked excavators, the ability to counter-rotate tracks (one forward, one backward) allows for extremely tight "spot turns" or "pirouettes," essential for repositioning in confined areas. Mastering this movement saves time and reduces ground disturbance.

V. Leveraging Technology and Accessories

Modern excavators are increasingly equipped with advanced technology and can utilize a wide range of attachments. Experienced operators maximize these tools.

1. Attachment Versatility:

Quick Couplers: Efficiently swapping between buckets, hammers, grapples, mulchers, and other attachments using hydraulic quick couplers is a key skill. Understanding the proper engagement and safety checks for each attachment is vital.

Optimizing Attachment Use: Knowing when to use a specific attachment (e.g., a riddle bucket for sorting, a vibratory plate compactor for backfill) can dramatically increase productivity and project quality.

Tiltrotators: For advanced operators, the tiltrotator attachment is a game-changer. It allows the bucket or attachment to rotate 360 degrees and tilt up to 45 degrees in two directions, enabling unparalleled versatility for grading, trenching, placing pipes, and working in tight spaces without constantly repositioning the machine. Mastering the complex joystick controls for a tiltrotator requires significant practice.

2. Telematics and Diagnostics:

Interpreting Data: Experienced operators can interpret telematics data (e.g., fuel consumption, idle time, fault codes) to optimize machine performance, identify maintenance needs, and contribute to fleet efficiency.

Onboard Diagnostics: Understanding in-cab diagnostic codes allows operators to identify and sometimes even troubleshoot minor issues, reducing downtime.

VI. Environmental Awareness and Sustainability

Advanced operators also contribute to environmentally responsible practices.

Minimizing Ground Disturbance: Using precision techniques to minimize the footprint of operations, reducing unnecessary ground disturbance and soil compaction.

Fuel Efficiency: Operating smoothly, avoiding excessive idling, and utilizing efficient digging techniques directly contributes to lower fuel consumption and reduced emissions.

Material Segregation: Efficiently separating waste materials for recycling during demolition or excavation processes.

Erosion Control: Understanding how to shape terrain and place material to prevent erosion and manage stormwater runoff.

Conclusion

The excavator is an extension of the operator's will, and its full potential is unlocked only through experience, continuous learning, and the mastery of advanced techniques. Beyond the basic mechanics of digging and lifting, true expertise lies in the ability to perform precision grading, navigate challenging terrain with confidence, handle materials with artful control, and strategically utilize the machine's diverse attachments and technological capabilities. For the seasoned operator, every hour in the cab is an opportunity to refine their touch, expand their repertoire, and transform complex challenges into showcases of efficiency and skill. By embracing these advanced techniques, operators not only elevate their own performance but also contribute significantly to the safety, profitability, and environmental stewardship of every project they undertake.

Post time:Sep-25-2020